Where the Hat Law was announced Population: 120,000

Old names: Timonion, Kastamone

In a sane world there is no way that Kastamonu, a sizeable town with a wealth of historic monuments as well as many huge and magnificent Ottoman konaks (mansions), would be so unfamiliar to foreign visitors. After all it’s only four hours’ drive north of Ankara. And, as the town where Atatürk chose to proclaim the Hat Law, it even deserves a footnote in modern Turkish history. But unfortunately for Kastamonu it lacks a really major attraction, a must-see sight that would land the knockout punch. What’s more, it’s sandwiched between Safranbolu and Amasya, both much more successful in blowing their own trumpets.

In a sane world there is no way that Kastamonu, a sizeable town with a wealth of historic monuments as well as many huge and magnificent Ottoman konaks (mansions), would be so unfamiliar to foreign visitors. After all it’s only four hours’ drive north of Ankara. And, as the town where Atatürk chose to proclaim the Hat Law, it even deserves a footnote in modern Turkish history. But unfortunately for Kastamonu it lacks a really major attraction, a must-see sight that would land the knockout punch. What’s more, it’s sandwiched between Safranbolu and Amasya, both much more successful in blowing their own trumpets.

Alas, to the recent blight of unsightly high-rises sullying the skyline has been added the paraphernalia required to construct a cable-car. If only Kastamonu could be protected from such developments.

The town’s modern name is a corruption of Castra Komneni, the castle of the Komnenis, the last of the Byzantine emperors. In 1057 Isaac I Komnenos was actually proclaimed emperor here.

Hat Law Embarrassed by foreigners’ mocking reaction to the fez, Atatürk passed the Hat Law in 1925 as part of his modernisation process. From then on men were forbidden to wear fezes and had to don şapkas, European-style hats with brims, instead. This may sound very innocent, even comical, but the fez-versus-hat issue was the headscarf problem of the 1920s and several unfortunates actually went to the gallows for refusing to change their headgear. Atatürk announced the new law in Kastamonu and in a small side room of the museum (closed Mondays) on Cumhuriyet Caddesi photos show him strolling around town with colleagues shortly afterwards. To set an example, they’re wearing a selection of hats in the awkwardly self-conscious way of a young woman showing off a new frock about which she has her doubts. (Unfortunately you may find this room locked for no very obvious reason).

The best place to start exploring is the main square, Nasrullah Meydanı, which is ringed with historic monuments and a great favourite with the local pigeons.

Most prominent of the monuments is the Nasrullah Cami (1506), which always has worshippers bustling in and out of it. In front its graceful ablutions fountain stands beneath a stone shelter, while behind it the bustling Munire Medresesi houses small craft workshops and a café. It’s a great place to seek out locally-woven tablecloths and other fabrics. On your way out don’t miss the giant dervish soup tureen propped up beside the exit.

Overlooking the square stand a pair of 15th-century hans, one of them reused as a mini shopping mall, and a disused hamam.

On the eastern side of town the İsmail Bey complex (1451-75) consists of a restored mosque, han and medrese, the latter now used as a small craftwork centre. Nearby an ancient tomb was cut into the rock at an unknown date.

Kastamonu town centre huddles in a valley between two hills, the first of them topped by Kastamonu Kalesi (Kastamonu Castle) which is visible from all around town. It’s one of those typically Turkish castles that has been built and rebuilt endlessly over the centuries, so although it was already in place in Byzantine times, most of what remains today dates from the Selçuk and Ottoman makeovers. Other than the walls there’s not that much to see inside. In any case to get the best view you’re better off climbing the hill on the other side of the valley. Here, beside a dinky 19th-century clocktower, an inviting tea garden offers a picture-postcard panorama over the old town.

On the hillside beneath the castle sits the lovely Yakup Ağa mosque complex (1547). Its medrese now houses crafts workshops while another part of the complex contains an EU-supported project to produce çekme helva, the local sweet that looks like fudge but tastes like pişmaniye.

On the hillside beneath the castle sits the lovely Yakup Ağa mosque complex (1547). Its medrese now houses crafts workshops while another part of the complex contains an EU-supported project to produce çekme helva, the local sweet that looks like fudge but tastes like pişmaniye.

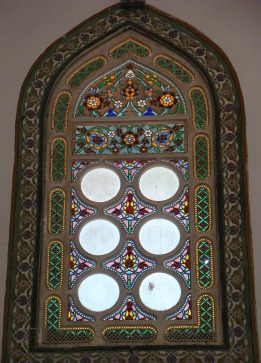

On the western side of town the Sinan Bey Cami dates back to 1571 and contains some lovely stained glass.

But all these mosques are thrown into the shade in terms of religious importance by the Şeyh Şaban–ı Veli complex. Şeya Şaban–ı Veli (1471-1579) was a poet and holy man who introduced the Halveti sect to the area. He’s buried in a shrine beside a mosque that is overlooked by two fine Ottoman mansions, one of them housing a small museum (closed Mondays). People come from miles around to draw water from the fountains that is said to be as sweet as that of Zemzem in Mecca. The complex is signposted on the western side of town.

In the early days of the Turkish Republic Kastamonu was certainly not off the beaten track and its government building is a stunning piece of First National architecture up steps at the top of a landscaped garden. With its arched windows and overhanging roofs, it’s one of the masterworks of Mehmed Vedat Tek (1873-1942), the architectural genius who also gave us Eminönü post office in İstanbul and the Grand Assembly building in Ankara.

The huge statue of Atatürk by Tankut Öktem that stands in front of it in Cumhuriyet Meydanı commemorates Kastamonu’s role in the War of Independence (1919-22) but was only erected n 1990.

The most unexpected hotel in Kastamonu, the Osmanlı Sarayı (Ottoman Palace), is housed in what was once the Belediye building, another fine example of First National style. Should the museum be closed (as it often is), the hotel lobby also displays photos of Atatürk in his new hat.

Those are the Kastamonu set-piece attractions but there are also any number of imposing Ottoman houses hiding in the back streets, some restored, others still awaiting a rescuer. The magnificent Liva Paşa Konağı contains a small ethnographic museum (closed Mondays), with rooms fitted out to enable visitors to imagine what life would have been like for the wealthy in 19th-century Kastamonu. Its most priced exhibit is the door from the mosque in nearby Kasaba that was stolen and then recovered.

Those are the Kastamonu set-piece attractions but there are also any number of imposing Ottoman houses hiding in the back streets, some restored, others still awaiting a rescuer. The magnificent Liva Paşa Konağı contains a small ethnographic museum (closed Mondays), with rooms fitted out to enable visitors to imagine what life would have been like for the wealthy in 19th-century Kastamonu. Its most priced exhibit is the door from the mosque in nearby Kasaba that was stolen and then recovered.

Several other mansions, including the luxurious Toprakçılar Konağı and the Sinan Bey Konak, have been converted into hotels. Yet another houses a restaurant – the Eflanili Konağı – which looks a little lost amid its innumerable rooms. Many houses are simply falling down.

Sleeping

Kurşunlu Hanı Hotel housed in restored han overlooking Nasrullah Meydanı. Tel: 0366-214 2737

Sinanbey Konağı Tel: 0366-212 6021

Toprakçılar Konakları Tel: 0366-212 1812

Otel Mütevelli Standard business-class hotel in modern building. Tel: 0366-212 2018.

Transport info

Kastamonu is four hours (240km) by bus from Ankara and nine hours (550km) from İstanbul.

There are frequent buses to Kastamonu from Sinop and İnebolu and onward connections to Amasya and Karabük (for Safranbolu).

Dolmuşes also link Kastamonu with Pınarbaşı.

To get to Kasaba you need to take a Daday bus as far as Subaşı and then walk the last five km.

Day trip destinations

Stained glass in Sinan Bey Cami

Stained glass in Sinan Bey Cami

Stained glass in Sinan Bey Cami

Stained glass in Sinan Bey Cami